CPA

Intermediate Leval

Economics November 2017 Suggested Solutions

Revision Kit

| ➦ | Economics-September-2015-Pilot-Paper |

| ➦ | Economics-November-2015-Past-Paper |

| ➦ | Economics-May-2016-Past-paper |

| ➦ | Economics-November-2016-Past-Paper |

| ➦ | Economics-November-2017-Past-paper |

| ➦ | Economics-May-2017-Past-paper |

| ➦ | Economics-November-2018-Past-paper |

| ➦ | Economics-May-2018-Past-paper |

| ➦ | Economics-May-2019-Past-paper |

| ➦ | Economics-November-2019-Past-paper |

| ➦ | Economics-November-2020-Past-paper |

| ➦ | Economics-December-2021-Past-paper |

| ➦ | Economics-May-2021-Past-paper |

| ➦ | Economics-August-2021-Past-paper |

QUESTION 1a

Time Horizon: Short-term plans typically cover a period of up to one year.

Focus: These plans are concerned with the immediate future and address the most pressing issues and objectives. They are often detailed and specific, focusing on day-to-day or month-to-month activities.

Characteristics: Short-term plans are crucial for achieving quick wins, addressing urgent challenges, and ensuring that day-to-day operations run smoothly. They are more tactical in nature and can be adjusted or revised frequently to respond to changing circumstances.

Time Horizon: Medium-term plans usually cover a time frame between one to five years.

Focus: These plans bridge the gap between short-term and long-term planning. They involve more strategic thinking and often aim to achieve specific milestones or objectives that contribute to the organization's long-term vision.

Characteristics: Medium-term plans provide a balance between short-term agility and long-term vision. They involve a more comprehensive approach than short-term plans and may include initiatives such as expanding market share, launching new products, or implementing major process improvements.

Time Horizon: Long-term plans encompass a time frame of five years or more.

Focus: These plans focus on the overall vision and direction of the organization. Long-term planning involves setting ambitious goals, defining the organization's purpose, and developing strategies to sustain and grow the business over an extended period.

Characteristics: Long-term plans are strategic in nature and require a deep understanding of market trends, competitive landscapes, and potential future challenges. They involve substantial investment and commitment and may encompass major initiatives such as entering new markets, developing new technologies, or significantly expanding the organization.

QUESTION 1b

1. Giffen Goods:

Giffen goods are exceptional cases where the demand for a good increases as its price rises, seemingly violating the law of demand. The classic example is the inferior staple food in times of extreme poverty. As the price of the staple rises, consumers may reduce their consumption of more expensive alternatives and buy more of the staple, leading to an upward-sloping demand curve.

2. Veblen Goods:

Veblen goods are luxury goods for which demand increases as the price increases. The conspicuous consumption aspect plays a role here; individuals may desire these goods more when their high prices signal prestige or exclusivity. In such cases, the demand for the good is not solely based on its utility but on the status it confers.

3. Collector's Items:

Certain goods, like rare coins, stamps, or limited edition items, may see an increase in perceived utility as the quantity possessed increases. Collectors often derive satisfaction from the uniqueness or rarity of each additional item, and the marginal utility might not diminish in the traditional sense.

4. Experience Goods:

Some services or goods provide experiences where the enjoyment or utility may increase with repetition. For example, watching a movie or reading a book may become more enjoyable upon repeated viewings or readings.

5. Nostalgia and Sentimental Value:

Certain goods may have sentimental or nostalgic value, and individuals may derive increasing satisfaction from owning additional units, especially if they have personal or emotional attachments to those items.

QUESTION 1(c)

1. Medium of Exchange:

Money facilitates the exchange of goods and services by serving as a universally accepted medium of exchange. In a barter system, direct exchange of goods and services requires a double coincidence of wants. Money eliminates this need, making transactions more convenient.

2. Unit of Account:

Money provides a standard unit for measuring and comparing the value of different goods and services. It simplifies the process of pricing and helps individuals make informed decisions about the relative value of items.

3. Store of Value:

Money serves as a way to store wealth over time. It allows individuals to hold onto their purchasing power until they decide to spend or invest. This function helps in saving and planning for future expenses.

4. Standard of Deferred Payment:

Money enables transactions where payment is made at a future date. This function is essential for credit transactions and contracts, providing a stable medium for honoring financial obligations over time.

5. Measure of Value:

Money allows for the measurement of value in a consistent and standardized manner. It aids in comparing the relative worth of goods and services, facilitating economic decision-making.

QUESTION 1(d)

2. Equitable Distribution: The government has the potential to ensure a more equitable distribution of resources and wealth, reducing income inequality and addressing social welfare concerns.

3. Stability and Predictability: Long-term planning can lead to greater economic stability. The government can implement policies to control inflation, stabilize prices, and avoid market fluctuations.

4. Focus on Public Welfare: The government can prioritize public welfare over profit motives, leading to investments in education, healthcare, and social services.

5. Strategic Planning for Key Industries: The government can strategically plan and invest in key industries deemed crucial for national development, such as infrastructure, technology, and defense.

1. Lack of Efficiency: Centralized planning can lead to inefficiencies due to bureaucratic processes, lack of competition, and a lack of incentives for innovation.

2. Limited Consumer Choices: Consumers may have limited choices as the government determines production and distribution, leading to shortages of certain goods and services.

3. Slow Response to Changes: The system may struggle to adapt to changing economic conditions or respond quickly to emerging market trends.

4. Bureaucratic Corruption: Centralized control can lead to corruption within the bureaucratic system, influencing decision-making for personal interests.

5. Lack of Incentives for Innovation: Without market competition, there may be a lack of incentives for businesses to innovate or improve efficiency.

6. Information Gaps: Central planners may lack accurate and timely information about local conditions and consumer preferences, leading to suboptimal resource allocation.

7. Potential for Authoritarianism: Central planning often goes hand in hand with a high degree of government control, potentially limiting political freedoms and individual rights.

QUESTION 2(a)

Businesses often make investment decisions based on the prevailing interest rates. Lower interest rates encourage businesses to undertake projects, expand operations, and invest in capital goods. Higher interest rates may lead to a decrease in investment due to increased borrowing costs.

Interest rates influence consumer behavior. Lower interest rates on loans, such as mortgages and car loans, can boost consumer spending. Conversely, higher interest rates may lead to reduced consumer borrowing and spending, impacting sectors like housing and durable goods.

Central banks use interest rates as a tool to control inflation. Higher interest rates can be employed to cool down an overheating economy and curb inflationary pressures by reducing spending and borrowing. Lower interest rates may be used to stimulate economic activity during periods of low inflation or recession.

Interest rates affect the return on savings and investments. Higher interest rates offer greater returns on savings accounts, bonds, and other fixed-income instruments, encouraging saving. Lower interest rates may lead to a shift towards riskier assets in search of higher returns.

The housing market is highly sensitive to interest rates. Lower interest rates make mortgages more affordable, leading to increased demand for homes. Higher interest rates can cool down the housing market by making mortgages more expensive.

Interest rates influence exchange rates. Higher interest rates attract foreign capital seeking better returns, leading to an appreciation of the currency. Lower interest rates may lead to a depreciation of the currency as capital flows out in search of higher yields elsewhere.

Interest rates affect the cost of capital for businesses. Lower interest rates can enhance business profitability by reducing interest expenses, while higher interest rates may increase costs and reduce profitability.

Governments often borrow money by issuing bonds. Interest rates affect the cost of servicing government debt. Higher interest rates increase the cost of debt, potentially impacting government budgets and fiscal policies.

Interest rates play a key role in maintaining overall economic stability. Central banks use interest rate policies to manage economic cycles, promoting growth during downturns and preventing overheating during periods of high economic activity.

Central planners may lack accurate and timely information about local conditions and consumer preferences, leading to suboptimal resource allocation.

QUESTION 2(b)

Developing and implementing effective debt management strategies can help countries optimize their borrowing and repayment schedules. This includes assessing the terms and conditions of loans, considering longer maturities, and negotiating favorable interest rates.

Ensuring transparency and accuracy in reporting debt-related information is essential. Countries should provide timely and comprehensive data on their external debt to build confidence among creditors and investors. Accurate information enables better-informed decision-making.

Relying on a diverse set of funding sources can reduce vulnerability to external shocks. Countries should explore alternative financing mechanisms, such as foreign direct investment (FDI), grants, and concessional loans, to complement traditional borrowing.

Increasing efforts to mobilize domestic resources can help reduce dependence on external borrowing. Effective tax policies, improved tax administration, and efforts to curb illicit financial flows can contribute to a more robust domestic revenue base.

Prioritizing investments in productive sectors that contribute to economic growth and generate revenue is crucial. Infrastructure projects and investments in sectors with high potential for returns can help countries service their debt through increased economic activities.

Focusing on export-led growth can improve a country's capacity to earn foreign exchange and service external debt. Policies that promote export-oriented industries, diversification of exports, and improvements in trade logistics can enhance a country's external balance.

Adopting and adhering to prudent fiscal policies is essential. Governments should avoid excessive spending, especially on non-productive areas, and work towards achieving fiscal discipline to prevent the accumulation of unsustainable levels of debt.

Strengthening institutional capacity for debt management, economic planning, and financial governance is crucial. Capacity building measures can help countries negotiate better loan terms, assess risks, and implement effective policies to manage debt sustainability.

Countries should actively negotiate with creditors to secure favorable terms, including lower interest rates, longer repayment periods, and grace periods. Engaging in debt restructuring when necessary can help alleviate immediate repayment pressures.

Engaging in international collaboration and seeking support from multilateral institutions can be beneficial. Working with international partners, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, can provide access to financial assistance, technical expertise, and policy advice.

Developing contingency plans to address potential external shocks can enhance a country's resilience to economic downturns. This includes creating buffers, such as sovereign wealth funds or reserves, to mitigate the impact of external shocks on debt sustainability.

Regularly conducting debt sustainability assessments with the help of international financial institutions can provide valuable insights. These assessments can guide policymakers in making informed decisions about their borrowing strategies and debt management practices.

QUESTION 2(c)

| Commodity A | Commodity B | Commodity C | |||

| Unit Price (Sh) 75 52 |

Quantitydemanded (Units) 923 1,568 |

Unit price (Sh.) 14 21 |

Quantity demanded (Units) 350 620 |

Unitprice (Sh.) 28 24 |

Quantity demanded (Units) 540 600 |

QUESTION 3(a)

QUESTION 3(b)

A successful promotional campaign highlighting the nutritional benefits of product X leads to an increase in the quantity demanded, shifting the demand curve from D0 to D1. Additionally, the price for product X increases from P1 to P2.

The discovery of a new use for product X increases the demand, shifting the demand curve from D to D1. Simultaneously, bad weather conditions negatively impact supply, causing a leftward shift from S to S1.

An increase in government subsidy increases the supply of product X due to reduced production costs, shifting the supply curve from S to S1. Conversely, a reduction in the price of substitute product Y decreases the demand from D to D1.

QUESTION 4(a)

QUESTION 4(b)

Under the cardinal approach, the horizontal line labeled PxMUₘ (price of commodity x times the constant utility of money) represents the constant utility of money weighted by the price of commodity x. Simultaneously, the MUm curve illustrates the diminishing marginal utility of commodity X.

The intersection of the Px∙MUₘ line and the MUm curve occurs at point E, where MUₓ (Marginal Utility of commodity X) equals Px∙MUₘ. This point signifies the consumer's equilibrium.

Points below E indicate that MUₓ < Px∙MUₘ, suggesting that the consumer can increase satisfaction by reducing the purchase of commodity x.

Conversely, points above E signify MUₓ > Px∙MUₘ. In such cases, exchanging money income for more of commodity x would increase satisfaction per unit of the commodity.

The consumer optimally allocates their income to achieve equilibrium at point E, balancing marginal utilities and prices. This graphical representation showcases how the consumer makes choices to maximize satisfaction within the constraints of their budget.

This cardinal approach emphasizes the quantitative aspect of utility and provides insights into how consumers adjust their consumption to reach the point of equilibrium.

The ordinal approach to consumer behavior introduces the concept of indifference curves, which are graphical representations of points where a consumer is indifferent to different combinations of two commodities. These points represent the same level of satisfaction for the consumer.

In the ordinal approach, the consumer's equilibrium is achieved at the point where the budget line is tangent to an indifference curve. Consider a scenario where a consumer has a choice between two commodities, A and B, and is allocating their income between these commodities.

Assuming the consumer spends their entire income on A and B, the equilibrium point, denoted as D, represents the combination of units of A and B that maximizes utility. At this point, the budget line CD is tangent to an indifference curve.

The consumer chooses the combination represented by point D, where the budget line is tangent to the indifference curve. This point signifies the highest level of satisfaction achievable within the budget constraint.

Point D is referred to as the point of consumer equilibrium. Here, the consumer has maximized utility given the budget constraint. The indifference curve represents all the combinations of A and B that provide the same level of satisfaction.

The ordinal approach emphasizes the ranking of preferences through indifference curves, allowing for a graphical representation of consumer choices. In this equilibrium, the consumer optimally allocates their budget to achieve the highest possible satisfaction level, given the preferences represented by the indifference curves.

This analysis highlights the role of preferences and choices in determining consumer equilibrium under the ordinal approach.

QUESTION 5(a)

QUESTION 5(b)

QUESTION 5(c)

QUESTION 6(a)

This concept is rooted in the economic theory of marginal utility, which quantifies the additional satisfaction gained from consuming one more unit of a good or service. Individual preferences vary, and as consumers acquire more of a good or service, the marginal utility tends to diminish, influencing their willingness to spend.

In the diagram, the consumer's willingness to pay is represented by the straight-line demand curve, labeled as Ap. Additionally, the curve AF indicates the utility derived from each successive unit of the commodity. The market price, at which consumers make their purchases, is denoted by BC.

At the market price BC, consumers buy CE units. The total utility derived by consumers from OC units is visually represented by the area CADC. Consumers, however, pay only BCDE, resulting in the total consumer surplus represented by the shaded area ABD.

On the other side, producer surplus is the difference between the amount a producer is willing to supply goods for and the actual amount received in the trade. In the diagram, this is denoted by the region BCD above the market price. It is a measure of producer welfare.

QUESTION 6(b)

QUESTION 6(c)

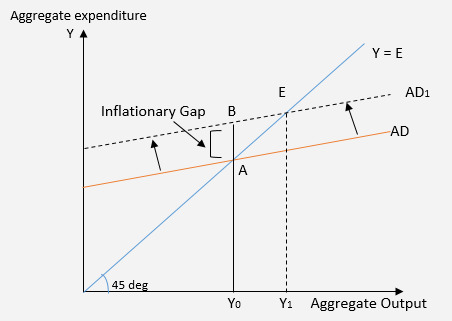

In the diagram, the inflationary gap is illustrated by the situation where aggregate expenditure exceeds aggregate output at full employment ( Y0 to Y1 ). This excess demand puts upward pressure on prices, necessitating an increase to ration the limited goods available in the economy.

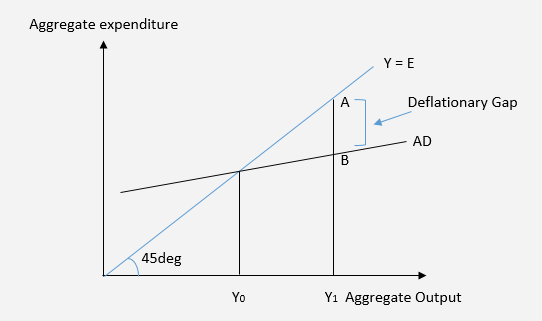

A deflationary gap represents the difference between the full employment output level and the actual output, often observed during economic recessions. This gap indicates substantial unemployment and underutilization of resources. It is also known as a negative output gap.

The deflationary gap is highlighted by the distance (AB) between the 45° line and the aggregate demand line (AD) at full employment. In such scenarios, prices need to be reduced to stimulate demand, moving the economy from ( Y0 to Y1 ).

QUESTION 7(a)

QUESTION 7(b)

Formula:

Characteristics: Inelastic demand typically characterizes goods or services that are necessities, have few substitutes, or are habit-forming. Consumers are less likely to reduce their consumption significantly in response to price increases.

Definition: Unitary elasticity of demand occurs when the percentage change in quantity demanded is exactly equal to the percentage change in price. In this case, the elasticity coefficient is equal to 1 (|Ed| = 1).

Formula:

Characteristics: When demand is unitary elastic, the total expenditure on the good remains constant as price changes. Consumers adjust their quantity demanded in such a way that the increase in spending due to a price increase is offset by the decrease in spending due to a quantity decrease.

QUESTION 7(c)

| Gross National Product (at market price) Depreciation allowance Indirect taxes less subsidies Business taxes Personal income taxes Government transfers Retained profit |

3,992 570 524 214 763 693 230 |

QUESTION 7(d)

Definition and Measurement: Developing countries often have a significant informal sector that may not be easily measurable or included in official statistics. This can lead to underestimation of the actual national income.

Data Collection: Collecting accurate and comprehensive data on income can be challenging in developing countries due to limited resources, inadequate statistical infrastructure, and difficulties in reaching remote areas.

Reliability: The reliability of the data collected may be questionable, leading to potential inaccuracies in estimating national income.

Subsistence Farming: In many developing countries, a large portion of the population is engaged in subsistence farming. Estimating the value of output in this sector can be complex, as it may not be fully monetized.

Barter Economy: Non-market transactions, such as barter arrangements or services exchanged within communities, are prevalent in some developing countries. These transactions may not be easily quantifiable in monetary terms.

Underground Economy: Illicit activities, informal trading, and other unrecorded economic transactions are common in developing countries. Estimating their contribution to national income is challenging due to the lack of official documentation.

Technological Constraints: Limited access to technology and modern infrastructure in some developing countries may hinder the accurate measurement of income-generating activities.

Inequality: Developing countries often experience high levels of income inequality. Failing to account for this inequality can result in an inaccurate representation of the overall economic well-being of the population.

Transfer Pricing: Multinational corporations operating in developing countries may engage in transfer pricing, making it difficult to accurately attribute income generated within the country to the national income.

Currency Fluctuations: Developing countries may experience volatile exchange rates, affecting the conversion of income into a common currency for international comparisons.

Natural Resource Depletion: Developing countries often rely heavily on natural resources. Failing to account for environmental degradation and the depletion of resources can lead to an overestimation of national income.

Price Distortions: Inflation and frequent price changes can distort the real value of income, affecting the accuracy of national income estimates.

| ➧ | Financial Accounting -September-2015-Pilot-Paper |

| ➧ | Financial Accounting -November-2015-Past-Paper |

| ➧ | Financial Accounting -May-2016-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Financial Accounting-November-2016-Past-Paper |

| ➧ | Financial Accounting-November-2017-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Financial Accounting-May-2017-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Financial Accounting-November-2018-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Financial Accounting-May-2018-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Financial Accounting-May-2019-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Financial Accounting-November-2019-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Financial Accounting-November-2020-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Financial Accounting-December-2021-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Financial Accounting-April-2021-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Financial Accounting-August-2021-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Quantitative Analysis -September-2015-Pilot-Paper |

| ➧ | Quantitative Analysis-November-2015-Past-Paper |

| ➧ | Quantitative Analysis-May-2016-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Quantitative Analysis-November-2016-Past-Paper |

| ➧ | Quantitative Analysis-December-2017-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Quantitative Analysis-May-2017-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Quantitative Analysis-November-2018-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Quantitative Analysis-May-2018-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Quantitative Analysis-May-2019-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Quantitative Analysis-November-2019-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Quantitative Analysis-November-2020-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Quantitative Analysis-December-2021-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Quantitative Analysis-April-2021-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Quantitative Analysis-August-2021-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Introduction to Law and Governance-September-2015-Pilot-Paper |

| ➧ | Introduction to Law and Governance-November-2015-Past-Paper |

| ➧ | Introduction to Law and Governance-May-2016-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Introduction to Law and Governance-November-2016-Past-Paper |

| ➧ | Introduction to Law and Governance-May-2017-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Introduction to Law and Governance-November-2017-Past-Paper |

| ➧ | Introduction to Law and Governance-November-2018-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Introduction to Law and Governance-May-2018-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Introduction to Law and Governance-May-2019-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Introduction to Law and Governance-November-2019-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Introduction to Law and Governance-November-2020-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Introduction to Law and Governance-December-2021-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Introduction to Law and Governance-April-2021-Past-paper |

| ➧ | Introduction to Law and Governance-August-2021-Past-paper |

| ➫ | Public finance & taxation-September-2015-Pilot-Paper |

| ➫ | Public finance & taxation-November-2015-Past-Paper |

| ➫ | Public finance & taxation-May-2016-Past-paper |

| ➫ | Public finance & taxation-2016-Past-Paper |

| ➫ | Public finance & taxation-November-2017-Past-paper |

| ➫ | Public finance & taxation-May-2017-Past-paper |

| ➫ | Public finance & taxation-November-2018-Past-paper |

| ➫ | Public finance & taxation-May-2018-Past-paper |

| ➫ | Public finance & taxation-May-2019-Past-paper |

| ➫ | Public finance & taxation-November-2019-Past-paper |

| ➫ | Public finance & taxation-November-2020-Past-paper |

| ➫ | Public finance & taxation-December-2021-Past-paper |

| ➫ | Public finance & taxation-April-2021-Past-paper |

| ➫ | Public finance & taxation-August-2021-Past-paper |

CPA past papers with answers